Arendt: The Banality of Evil

Graham Leach-Krouse ∙ Philo100

- Banality

- The condition or quality of being banal; triviality.

- Something that is trite, obvious, or predictable; a commonplace.

unoriginality, predictability, dullness, ordinariness, triviality, staleness, vapidity, triteness cliché, commonplace, platitude, truism, bromide (informal), old chestnut, stock phrase

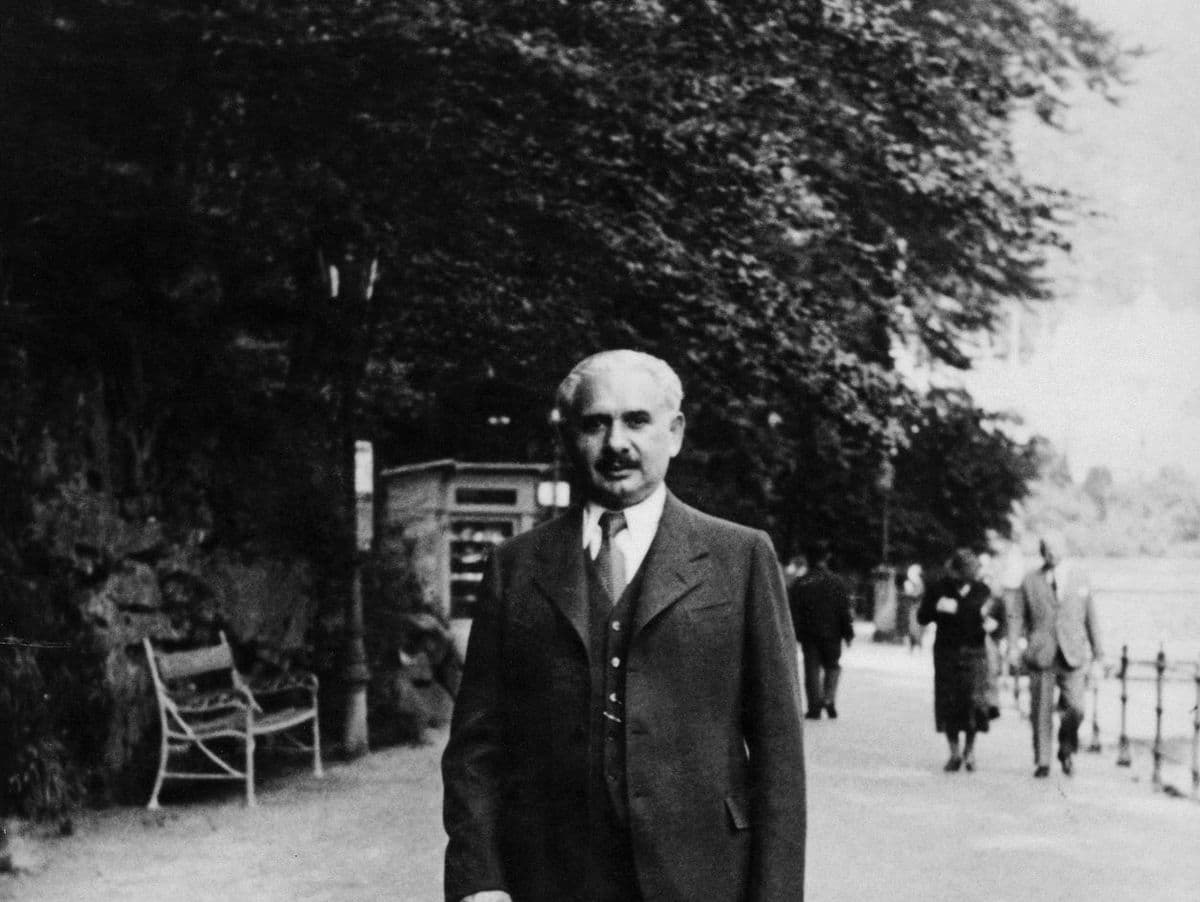

Adolph Eichmann

Joined Nazi party in 1932, on advice of family friend.

“Weekend Nazi” until 1933 when laid off from Vacuum Oil.

Transferred to “Jewish Department” of SS Intelligence, 1934.

Too bored at Dachau

By 1938, working on logistics of “voluntary” Jewish emigration.

1939, Nazi policy shifts towards forced deportation. Eichmann assumes control of the Central Office for Jewish Emigration.

Horrendous conditions on trains, planning failures, lead to death rate of around 1/3.

Eichmann focuses mainly on economic and military impact of operations.

1941, attends Wannsee conference, to help coordinate and organize the final solution.

Eichman oversees stenographer, prepares records.

Takes responsibility for seizing Jewish property, scheduling trains that transport victims to extermination camps.

Post-war, manages to flee to Argentina, becomes a department head at Mercedez-Benz.

May 11th, 1960, Captured by Zvi Aharoni, extradited to Isreal for trial.

Arendt, eager to test her theories on the totalitarian mindset, and “having witnessed little of the Nazi regime directly”, volunteers to cover the trial for the New Yorker.

Offer accepted.

Recall...

Eichmann's character: weirdly normal.

What does it mean to be “weirdly normal”?

Unexpectedly normal. Just some guy?

Excessively normal? But what does that mean?

Personality quirks:

- Bad memory, “utter ignorance of everything that was not directly, technically and bureaucratically, connected with his job”

- Not very good at imagining other people's viewpoints.

- Enjoys clichés. Can't see contradictions.

Eichmann's Memory

Not an “I cannot recall”, pleading of the fifth kind of thing.

Couldn't remember dates that war was declared, couldn't remember when Germany invaded Russia.

Couldn't recall the content of the discussions at Wannsee.

What could he remember?

At the Wannsee conference, permitted to sit with Müller and Heydrich.

“That was the first time I saw Heydrich smoke and drink”

According to Arendt,

Eichmann remembered the turning points in his own career rather well, but [these] did not necessarily coincide with the turning points in the story of Jewish extermination or, as a matter of fact, with the turning points in history.”

Eichmann's Imagination

During examination by Isreli police, Eichmann attempts to paint a “hard luck” story, complaining about his bad luck, and how his failure to obtain a higher rank within the SS was not his fault.

Berthold Storfer

got almost 10,000 people out of Germany

He told me all his grief and sorrow: I said: ‘Well, my dear old friend, we certainly got it! What rotten luck!’

And I also said: ‘Look, I really cannot help you, because according to orders from the Reichsführer nobody can get out. I can’t get you out. Dr. Ebner can’t get you out. I hear you made a mistake, that you went into hiding or wanted to bolt, which, after all, you did not need to do.’

I forget what his reply to this was.

Eichman's Self-Consciousness

Digression: do we have a name for this part of the self?

Eichmann had an extraordinary ability to hold contradictory thoughts in his mind.

Makes a big fuss about how one should never take an oath, then immediately takes an oath.

Says that having five million deaths on his conscience “gives me extrordinary satisfaction” and that he will “jump into his grave laughing”, but also says he will gladly hang himself in public “as a warning example to for all anti-semites on this earth”

On the gallows, says that he is an Gottgläubiger (Adherent of Nazi “Positive Christianity”), but then promises, contra doctrine, that he'll see everybody on the other side.

As far as Eichmann was concerned, these were questions of changing moods, and as long as he was capable of finding, either in his memory or on the spur of the moment, an elating stock phrase to go with them, he was quite content, without ever becoming aware of anything like ‘inconsistencies.’

Officialese is my only language.”

What’s wrong with Eichmann?

The Comedy of the Soul-Experts

Half a dozen psychiatrists had certified him as ‘normal’— ‘More normal, at any rate, than I am after having examined him,’ one of them was said to have exclaimed, while another had found that [Eichmann's] whole psychological outlook, his attitude toward his wife and children, mother and father, brothers, sisters, and friends, was ‘not only normal but most desirable’”

The minister who had paid regular visits to him in prison after the Supreme Court had finished hearing his appeal reassured everybody by declaring Eichmann to be ‘a man with very positive ideas.’”

Behind the comedy of the soul experts lay the hard fact that [Eichmann's case] was obviously no case of moral let alone legal insanity.”

A Bad Morality?

Hard to say, because of Eichmann's psychology.

But

The first indication of Eichmann’s vague notion that there was more involved in this whole business than the question of the soldier’s carrying out orders that are clearly criminal in nature and intent appeared during the police examination, when he suddenly declared with great emphasis that he had lived his whole life according to Kant’s moral precepts, and especially according to a Kantian definition of duty.”

He then proceeded to explain that from the moment he was charged with carrying out the Final Solution he had ceased to live according to Kantian principles, that he had known it, and that he had consoled himself with the thought that he no longer ‘was master of his own deeds’”

So, perhaps aware that he was not acting morally.

Still motivated by obedience, though, even after Himmler and others had given up.

Arednt's Assessment

Despite all the efforts of the prosecution, everybody could see that this man was not a ‘monster,’ but it was difficult indeed not to suspect that he was a clown.”

He merely, to put the matter colloquially, never realized what he was doing…”

In principle he knew quite well what it was all about, and in his final statement to the court he spoke of the ‘revaluation of values prescribed by the [Nazi] government.’ He was not stupid. It was sheer thoughtlessness—something by no means identical with stupidity—that predisposed him to become one of the greatest criminals of that period.”

And if this is ‘banal’ and even funny, if with the best will in the world one cannot extract any diabolical or demonic profundity from Eichmann, that is still far from calling it commonplace.”

- Arendt's Second Theory of Evil

- (Banal) evil is extreme wrongdoing, resulting from a well-integrated incapacity for moral reflection and judgment in an otherwise healthy person.

- extreme wrongdoing

- well-integrated (part of the personality)

- otherwise healthy

Evaluation

Is this what's wrong with Eichmann?

Why not:

Evil is extreme wrongdoing, resulting from

a well-integrated incapacity for moral reflection and judgment in an

otherwise healthy person.

Arendt imagines a final tribunal:

You also said that your role in the Final Solution was an accident and that almost anybody could have taken your place, so that potentially almost all Germans are equally guilty. What you meant to say was that where all, or most all, are guilty, nobody is.

… even if eighty million Germans had done as you did, this would not have been an excuse for you. Luckily, we don’t have to go that far. You yourself claimed not the actuality but only the potentiality of equal guilt on the part of all.”

… there is an abyss between the actuality of what you did and the potentiality of what others might have done.”

This entails a form of “Moral Luck”: whether you are evil or not can be a matter of luck, out of your hands.

Arendt apparently embraces this conclusion.

If we don't, what do we make of this?

The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal.

From the viewpoint of our legal institutions and of our moral standards of judgment this normality was much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together for it implied—as had been said at Nuremberg over and over again by the defendants and their counsels—that this new type of criminal, who is in actual act hostis generis humani (an enemy of mankind), commits his crime under circumstances that make it well-nigh impossible for him to know or to feel that he is doing wrong.